Most crisis playbooks optimise for optics. Trust is rebuilt when leaders explain how decisions happened and change the structure that made them possible.

Most organisations treat a crisis like a fire.

Contain it. Control it. Move on.

That instinct is what destroys trust.

Because people aren’t judging you on whether a mistake happened. They’re judging you on whether you tell the truth about how it happened, and whether you fix the system that allowed it.

Luke Tobin, CEO of Unusual Group, puts it simply:

“Most crisis playbooks are built for optics, not truth. And people can feel the difference.”

The real shift leaders are missing

The old crisis model assumed you could control the narrative.

You can’t.

Information moves fast. Screenshots travel. Internal messages leak. Silence gets interpreted.

“Silence used to buy you time,” Luke says. “Now it creates suspicion.”

So the question has changed. It’s no longer “How do we make this go away?”

It’s “What does our response teach people about who we really are?”

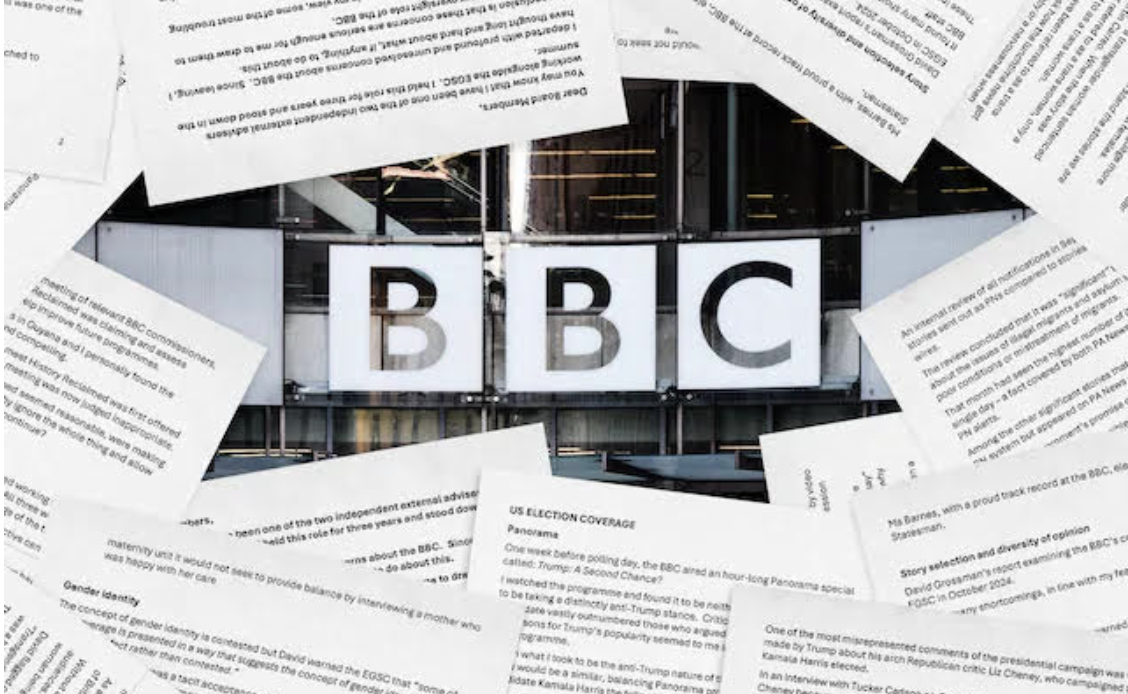

The Panorama controversy and the limits of damage control

The BBC’s Panorama controversy in late 2025 is a clear example of this shift. Criticism over editing in a Trump-related programme escalated into political pressure, a public apology, and senior resignations.

On the surface, that looks like accountability.

But accountability isn’t the same as repair.

“Resignations are visible,” Luke says. “They’re not systemic. They don’t explain how the decision happened or what changes, so it can’t happen again.”

Ali Newton-Temperley, COO of Unusual Group, agrees:

“When organisations treat crises as communications problems instead of governance problems, people feel it immediately. Staff feel it. Audiences feel it. And once the response looks performative, trust drops fast.”

The point isn’t that institutions must never make mistakes. The point is that trust breaks when people feel managed instead of respected.

The Trust Rebuild Test

When trust is damaged, there are only three questions that matter.

1) Truth

What happened, in plain language. No theatre. No fog.

2) Decision path

Who made the call, based on what information, and what controls failed.

3) Reform

What changes now, in structure and process, so the same failure can’t repeat itself.

If you can’t answer those three, your statement will land as spin, even if it’s written beautifully.

Apologies without explanation feel evasive.

Resignations without reform feel symbolic.

Statements without structural change feel performative.

And the irony is: the more polished it sounds, the less it’s believed.

What effective crisis leadership looks like now

The organisations that recover best do the opposite of instinct.

They open up, instead of closing down.

They welcome scrutiny, instead of resisting it.

They talk about decision-making, not just outcomes.

This isn’t just a media problem.

Employees judge leadership credibility through crisis behaviour.

Customers decide brand trust through response, not messaging.

Investors evaluate governance by what you show under pressure.

“A crisis is where leadership becomes most visible,” Ali says. “It reveals what’s protected, what’s sacrificed, and what’s negotiable.”

Why this matters now

Trust used to be granted to institutions with history, status or scale.

Now it’s earned through behaviour, repeatedly, and especially under pressure.

That makes transparency non-negotiable. Not as a gesture, but as a baseline.

Trust is the surface and legitimacy is the foundation. When legitimacy cracks, every decision becomes contested, and every mistake becomes a weapon

“Handled well, a crisis becomes a turning point,” Luke says. “It can strengthen culture and deepen loyalty. But only if you’re honest about the system, not just sorry about the outcome.”

A petition for an independent BBC governance review

In response to the Panorama controversy, Luke Tobin has launched a petition calling for an independent, public-facing review of BBC editorial governance and accountability.

The framing is simple: this isn’t anti-BBC, and it isn’t partisan. It’s pro-trust in a publicly funded institution.

If you agree that the BBC needs an independent, public-facing review of editorial governance, you can add your name here.

The final point

The crisis is rarely the thing that ends trust, but the cover-up instinct does.

In the next decade, the best-led organisations won’t be the ones that avoid mistakes.

The best-led organisations won’t be the ones that avoid mistakes.

They’ll be the ones who tell the truth about how it happened, and change what made it possible.

That’s what trust looks like now.

Increasingly, the response is the story.

.svg)

.jpg)

.jpg)